When we feel stress rising, and start to sense pain, headaches or tension, connecting with our breath can be an effective tool to counter that response. And as something we do over 20,000 times per day, breathing is worth some consideration.

But how we focus on breath matters and in my last few months of teaching I’ve become aware of the common misconception that deep breathing is always the best choice. For many of us trying to breathe deeply can make neck muscles work harder, increasing upper body stress.

The body has options as to how to breathe and adjusts according to task. Being able to differentiate between breathing techniques and to understand their unique benefits can be helpful.

The body has options as to how to breathe and adjusts according to task. Being able to differentiate between breathing techniques and to understand their unique benefits can be helpful.

- Quiet Breathing

- Cardio Breathing

- Deep Breathing

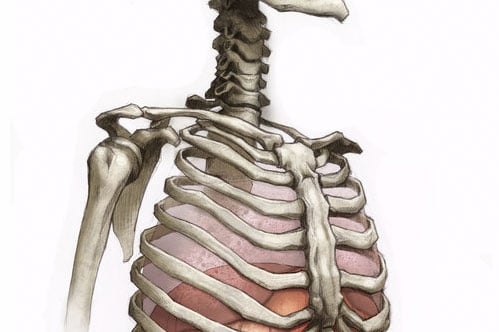

Quiet breathing, also referred to as tidal breathing is our breath pattern at rest which is highly efficient, using minimal muscles. The diaphragm and intercostal muscles expand the lungs and chest cavity to draw air in, and passively recoil to release air out. No energy is required on the exhale. We take in less than 1/4 of the volume of air that we would take in with our maximal breath, as this is all that is needed.

Cardio Breathing. The breath pattern changes when the need for oxygen increases and the body responds by increasing volume in the chest cavity. It does this in part by using muscles of the chest and neck, like the scalenes, and pectoralis minor muscles in order to lift the upper ribs and increase space. These are muscles that can be problematic in relation to neck tension if they are always active, but in this case their activation is an appropriate add on to the mechanics of tidal breathing. (There will be more on cardio breathing in the follow up blog).

Deep Breathing is commonly referred to as diaphragmatic or belly breathing. It is a focused breath that can be used to lower stress levels, bring on a parasympathetic nervous system response and is often used in meditation and yoga. This involves breathing into the abdominals and pelvis, while feeling the belly rise with long full inhales and exhales.

There is a time and a place for all of these breaths.

The problem regarding deep breathing is that it can be forceful. It can take a lot of muscular effort, particularly if the underlying tidal breath pattern is not optimal.

For example, if you have excess tension in the abs or pelvis (see Pelvic floor blog), then the diaphragm can’t drop enough and there is no way to increase volume without using the neck to elevate the ribs. You can experiment with an extreme version of this. Tighten your abs and gluteals. Take a few deep breaths. Where does the “work” go? Or try to really fully expand your belly on a deep breath. Your abdominals become active instead of responsive.

You may have to earn your way to diaphragmatic breathing.

Or you don’t have do it at all.

What is critical in regards to neck tension is that the breath pattern that you use constantly, tidal breathing, be as efficient as possible.

Next time you feel tension rising, pause.

- Take a deep breath if needed.

- Then simply become aware of your breath.

- Try to imagine the diaphragm dropping down as you inhale.

- Allow the abs to be soft enough to respond.

- Tighten and release your gluteals a few times, leaving them released.

- Imagine breathing into the pelvis as you inhale.

Hard to imagine your diaphragm? Watch this cool animation and you may find it easier to image.

Posture and stability can also limit our breath or make it less efficient. Experienced Pilates and Franklin Method teachers should be able to help you improve your posture and your breath pattern.

In my next blog I will look at current studies on cardio respiratory fitness and it’s rising status as a broad and critical marker of health.

Did you find this helpful? Confusing? Intriguing? I’d love to hear your feed back.

Laura Helsel

Director, Pilates Process

laura@pilatesprocess.ca